©Getty

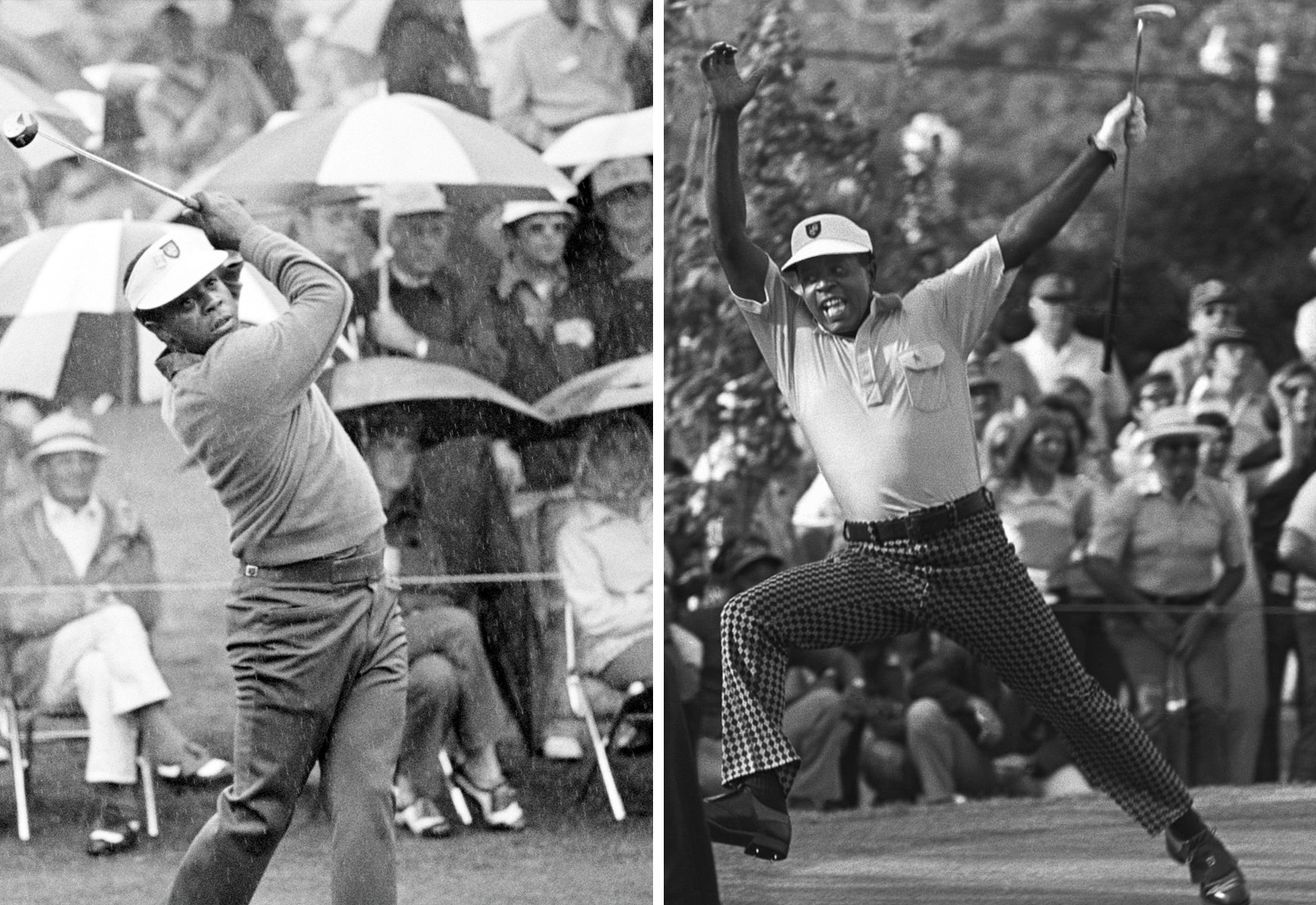

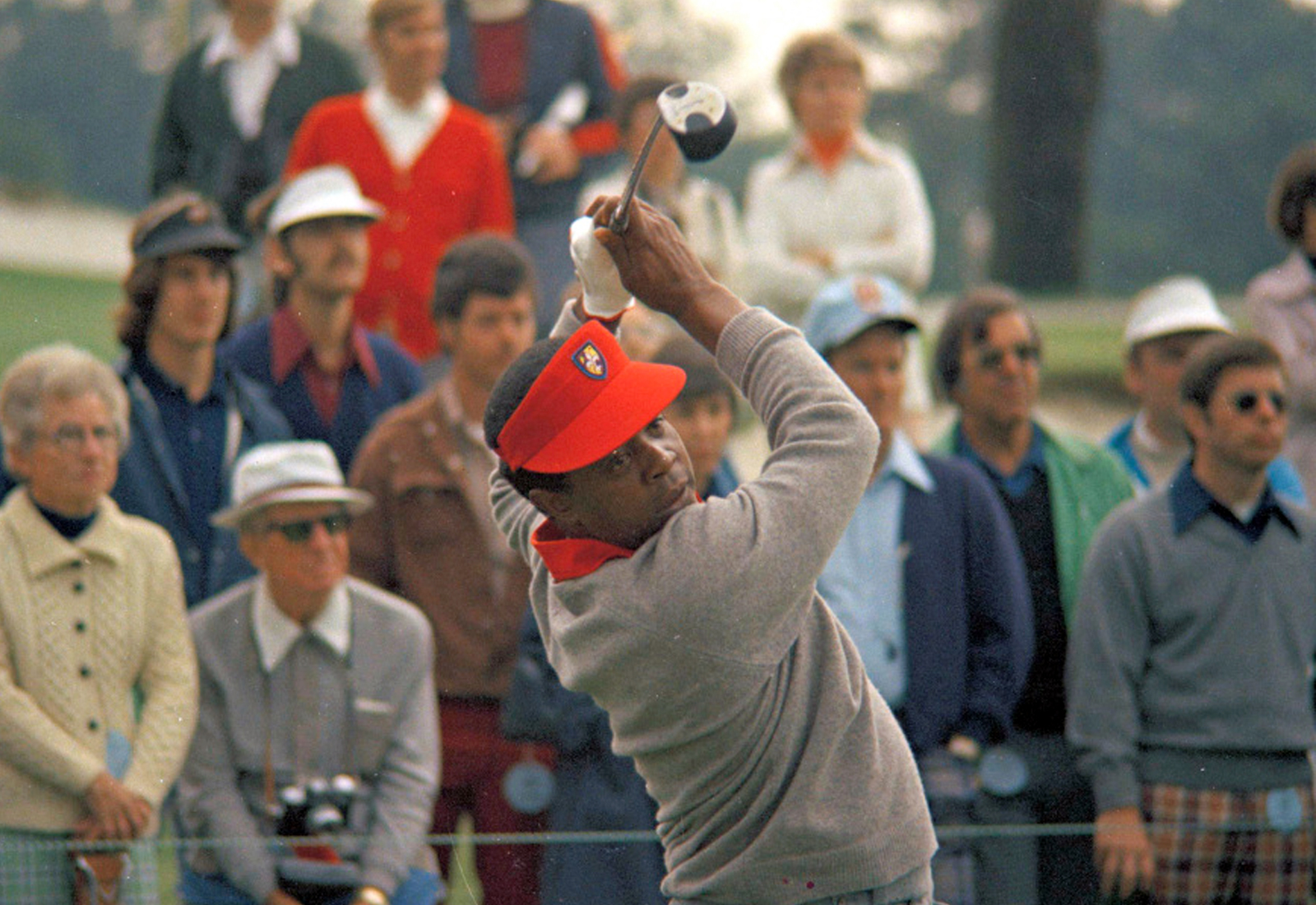

Nearly half a century ago, Lee Elder broke a major barrier when in 1975 he qualified for the Masters after winning the 1974 Monsanto Open at Pensacola in Florida, his maiden PGA Tour title.

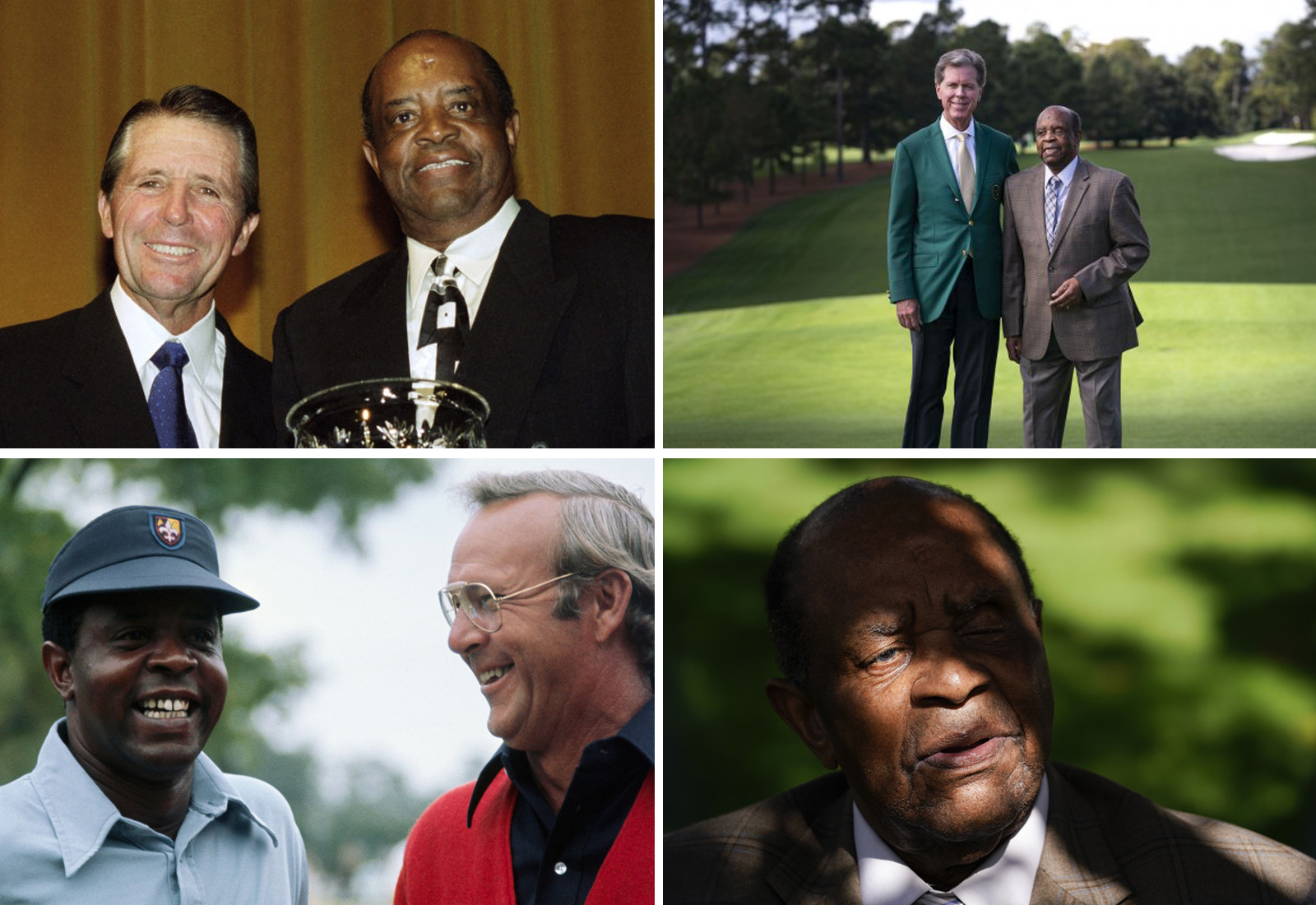

Until the Dallas native came to Augusta National, the only Blacks allowed were caddies and waiters, but while change doesn’t come along quickly on these hallowed grounds (The Masters, first played in 1934, didn’t extend an invitation to a Black competitor until Lee received one in 1975. The club didn’t admit its first Black member until 1990 and didn’t offer membership to women until 2012), on the 45th anniversary of his historic appearance, Elder was recognized with an invitation to become an honorary starter alongside the sport’s elder statesmen and long-serving ambassadors, 80-year-old Jack Nicklaus and 85-year-old Gary Player.

Elder was 40 when he made his Masters debut, which was probably too old for him to mount a challenge for victory. He missed the cut, however he did post a pair of Top 20 finishes in six Masters appearances

The youngest of eight siblings, Elder’s parents had died by the time he was 7-years-old. However, with the help of a brother who worked as a caddy, the youngster got into the game early, securing work at a golf club collecting stray balls and becoming a caddie himself when he was big enough.

©Getty

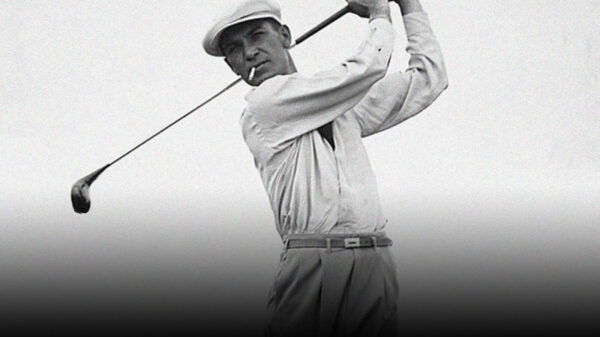

It gave him time to develop his own game, but he also received help after playing a match with heavyweight boxer Joe Louis in Cleveland and attracting the attention of Louis’s personal golf instructor, Ted Rhodes. Rhodes took Elder abroad to play in places like Jamaica, Venezuela and Cuba and most importantly, on the advice of Rhodes in 1966, after playing all his life with an unusual cross-handed grip, Elder changed to the standard Vardon grip. It would be a game changer. “He was like a father to me. Whatever success I have attained I owe to him,” Elder was quoted as saying about the impact Rhodes had on him in the Washington Post Magazine.

He continued to hone his skills while in the army (Elder placed second in the All-Service Tournament in 1960, and lost to future U.S. Open champion Orville Moody in the Sixth Army Championship). The Texan excelled in the Blacks’ United Golf Association tour, winning the UGA championship five times and during one stretch he had a brilliant run putting together 21 victories in 23 consecutive tournaments.

Owing his development more to hard work and diligence rather than natural skill, after raising enough money for Q-School in 1967, the young man joined the PGA Tour in 1968.

©Getty

There he experienced racism. Incidents included being forced to change clothes in his car at a Florida tournament as black people were not allowed in the clubhouse. Once at a tournament in Memphis, he was penalized after a spectator took his ball from the fairway.

And even though he received lots of accolades for The Masters, at the same time, because he received death threats leading up to that Grand Slam event, he rented two houses in Augusta during the week to share his time between them for safety.

In 1971, with the help of Gary Player (who reportedly had to petition John Vorster, South Africa’s prime minister to make it happen), Elder was able to compete in the South Africa PGA Championship at a time when the racist regime’s laws of apartheid required segregated everything. During his visit to Africa, he also took first place in the Nigerian Open tournament.

Elder did enjoy a lot of success. At 45, he was a member of the victorious 1979 US Ryder Cup team led by captain Billy Casper defeating Europe at The Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

©Getty

His best finishes in the majors were two 11th place results, one at the 1974 PGA Championship (at Tanglewood Park in Clemmons, North Carolina, where Lee Trevino won the first of his two PGA Championships, one stroke ahead of defending champion Jack Nicklaus) and the other 1979 US Open (at Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio, where Hale Irwin won his second U.S. Open title).

Winner of four PGA events and eight Sr. PGA tournaments, Elder’s career earnings as a pro golfer exceeded $2 million.

Through it all, both the man himself and golf fans most associate him with the racial breakthrough at The Masters.

“The opportunity to earn an invitation to the Masters and stand at that first tee was my dream and to have it come true in 1975 remains one of the greatest highlights of my career and life, so to be invited back to the first tee one more time to join Jack and Gary for next year’s Masters means the world to me,” Elder said at the announcement last year.

©Getty and Augusta National

As part of Augusta National’s announcement, chairman Fred Ridley said the club would be funding two golf scholarships at nearby Paine College, a historically Black school, as well as funding the start-up of a women’s golf program at the school.

“The courage and commitment of Lee Elder and other trailblazers like him inspired men and women of color to pursue their rightful opportunity to compete and follow their dreams,” Ridley said during a news conference at Augusta National. “But in reality, that opportunity is still elusive for many. We have a long way to go, and we can and we must do more.”